I started researching my family’s history when I was twelve. Three out of my four grandparents had lost an uncle in the Great War. For all but one, we barely knew their names. However, my grandmother had been raised on the stories of her mother’s brothers who had left Edmonton to serve in Europe, particularly Uncle Alec, who had died while serving with the PPCLI. She passed these stories onto her children, and my father passed the story of Uncle Alec on to me. Today, we spent the morning at Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, where Alec was buried after his death. Alec remains the present past for my family, reflecting the enduring loss felt by my great-grandmother, Helen, and his extended family.

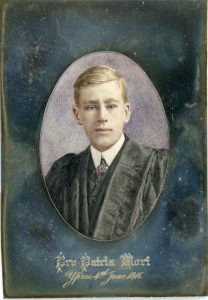

The facts are simple. Alexander Robertson McQueen was born on January 24th, 1893 in Edmonton, the second son of seven children. He enlisted on May 4th, 1915. At the time of enlistment, he was a student at the University of Alberta. He had blue eyes and light brown hair. He was 6’. From accounts sent to the family after his death, he was courageous, dutiful, and had a keen sense of humour. And, on June 4th, 1916, he died of wounds sustained during the Battle of Mont Sorrel, aged just twenty-three.

It felt almost ridiculous to approach a single loss amid the 10,794 graves that form Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery. The larger CWGC cemeteries and memorials approach death on a massive scale, making individual losses almost impossible to comprehend. One death is a tragedy, while the more than 54,000 names on the Menin Gate are somehow a backdrop for screaming British schoolchildren to practice the Macarena. I decided to approach Alec from a personal perspective, emphasizing a life outside of the war and a loss that extended far beyond the immediate McQueen family. Each grave in these cemeteries should be understood as a loss with lasting repercussions, rather than sheer statistics.

This isn’t to say that she remained in perpetual mourning. She travelled, married, had children, and lived a long, fulfilling life an ocean and half a continent away from these battlefields. She was, however, determined to keep the memory of her brother alive.

Through my great-grandmother’s determination to keep the memory of Alec alive, this site remains a present, painful loss. (full disclosure: I cried during my presentation.) Memories of her beloved older brother became intertwined with the narratives of sacrificial loss that shape our conception of the First World War. These individual soldier presentations embody the meaning of the CBF Study Tour. These individual stories emphasize the deeply personal nature of each loss, and reflect the enduring legacy of the world wars.

Alexandra McKinnon