I met my great-great uncle today.

Writing those words is making me cry again, so it’s a good thing we’ve had a good supply of Belgian and French chocolates since we arrived in France last Saturday. We’ve all been on an emotional roller coaster, and that’s the point of the experience. Each one of us is here to make personal connections to the histories we’re experiencing, and that’s important.

History is my bread and butter, both as a graduate student in history and as an interpreter at the Canadian War Museum. My job is to make connections with my audience and the history I’m introducing them to, whether it’s to link new Canadians with the stories of earlier immigrants who fought for Canada, or to tell young women about our grandmothers and great-grandmothers who pulled their own weight in the Canadian war effort. (There are other ways, but those two are dear to my heart.) As a public historian, how people make use of history is really interesting for me, and I find that now I’ve been selected for the Canadian Battlefields Foundation tour, what I’m finding in France and Belgium is surpassing my expectations.

We’re all making connections, and if you’ve read the previous entries written by my colleagues, you’ll know what kinds of links we’re established with the histories we’ve been taught, and with the sites we’re witnessing here. We’re honouring not only our own Canadian fallen, laid out to rest in the perfect garden cemeteries that are scattered throughout farmers fields not too unlike those we know at home. We’re also seeing the somber and intense German cemeteries, at the young men not unlike our own who died far from home. We’ve seen the many British and Commonwealth monuments, and we’re being reminded of the imperial project of war, and the larger context of the Canadians fighting alongside their colonial brethren. For me, what’s eye-opening are the encounters with the French – the countless poilus buried in the massive cemeteries that took our breath away, and with the modern day people who I’ve encountered and who live their lives surrounded not just with the physical reminders of the world wars, but the many more that happened before.

(As an aside, it’s hard to say exactly what’s struck me hardest before today. The Menin Gate, with its integration into the city of Ieper (modern Ypres), was moving. I felt goosebumps at Lochnagar Crater Memorial where the sight of crater too reminiscent of a caldera volcano reminded me of the terrors lurking under soldiers’ feet. When we visited the Leaning Virgin in Albert, better known as Notre Dame de Brebières, I could image soldiers whispering prayers as they marched beneath, hoping the legend of the Virgin finally tumbling down and ending the war would happen before they returned to the line. And, of course, finally being able to see Vimy Ridge was an experience that still doesn’t quite feel real.)

Our itinerary today continued where we left off yesterday, where we ended with the Battle of Amiens in early August 1918. We covered the last one hundred days of the war, although the point was made several times by our guides, Graham and Andrew, that at the time no one really realized the end of the war was coming so soon. Our first stop was in Monchy-le-Preux to see the Newfoundland memorial; I noticed after Andrew’s talk that the local French memorial was next door. Memorials are a particular interest of mine, and I’ve been noticing and photographing the French memorials in several areas. This one was especially poignant because instead of the typical poilu, it was a woman and child looking down at the helmet representing their missing husband and father. If that isn’t representing the loss of war, I don’t know what will.

The theme of the missing has been heavily on my mind, because that could’ve been the fate of my great-great uncle, and this was the day I’d have the honour to visit his grave. Francois Houle was a member of the 24th Battalion, and he was killed at the age of 18 on August 27, 1918, in the early days of the Second Battle of Arras. He joined the CEF after four failed attempts due to being underage, and his stubbornness is something I identify with in regards to striving for what I want. He was originally listed as missing, and his body wasn’t reported as found until September 9 – incidentally seventy years to the day before I was born. We’ve seen hundreds, if not thousands, of tombstones belonging to unknown soldiers, and then there’s the names of the missing inscribed on memorials. It’s struck me time and time again that our family might’ve only been left with a name on the wall if circumstances had been different, and that’s left me with a strange, almost grateful feeling in my chest to whoever those people were who found Francois’ body over ninety years ago.

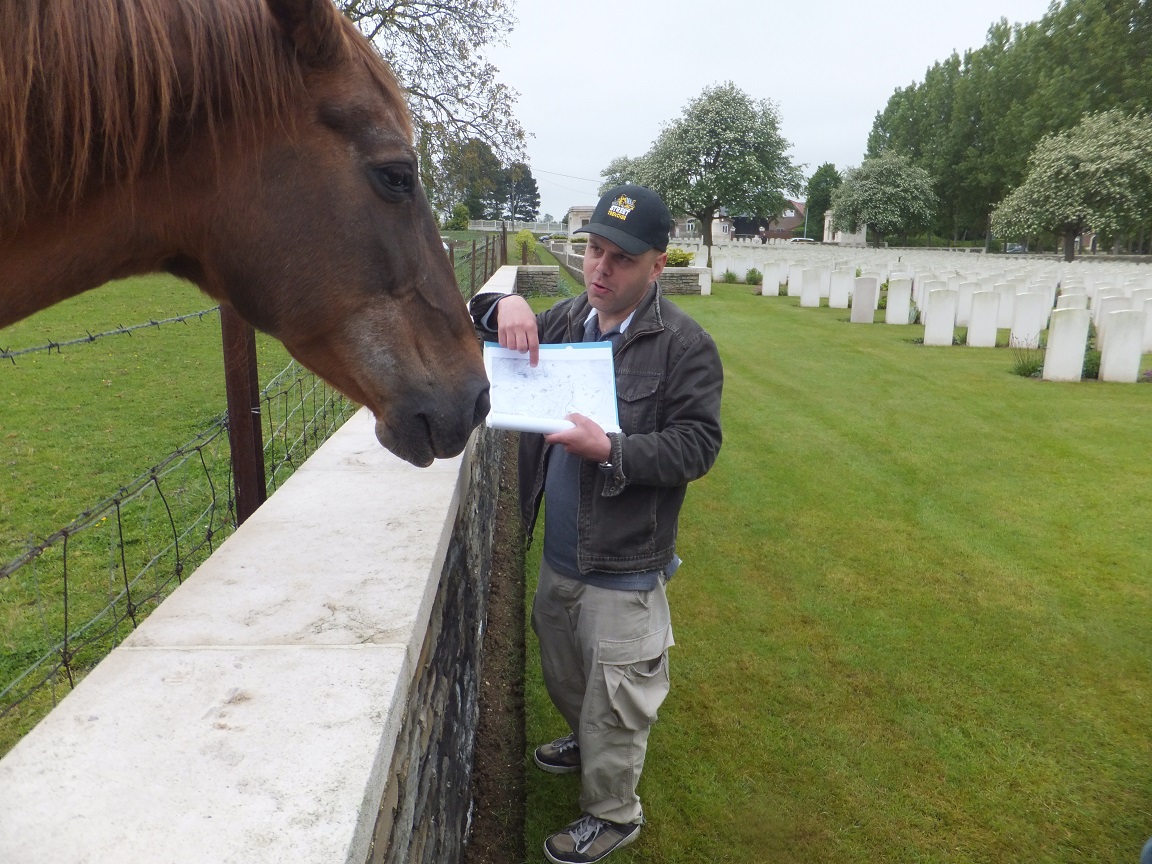

Our second stop of the day at Vis-en-Artois just compounded that feeling. We went to Vis-en-Artois, with another memorial for the British, Irish and South African soldiers whose bodies were never found or identified. Andrew shared details about the start of the Battle of Arras, and highlighted the involvement of the 22nd and 24th Battalions. The scene was set, and as we got back into our vans to begin the trek over toward Quebec Cemetery, near Cherisy, I felt nervous. I confessed to Graham before we left that I was feeling anxious, but it wasn’t performance anxiety. It was expectation.

Quebec Cemetery is set in a farmers field, probably by a first aid post set up during the battle, where many of the fallen members of the 2nd Division were buried. The cemetery is small compared to others we’ve visited, but it was easy enough to locate Francois’ grave. Andrew was giving a few words about the 24th Battalion, or maybe it was about the cemetery itself, but I don’t remember. All I really remember was this sudden and overwhelming sadness, and I just started to cry.

There are some wonderful people on this tour, I should mention, and they listened as I managed to catch my breath, wipe my face, and get through my presentation. Francois is my great-grandfather’s younger brother, and he and another great-great uncle both enlisted for the First World War. Eli came home, and Frank died in a farmer’s field outside of Cherisy. I shared his story to my new friends, and then I turned to Francois’ grave to tell him about his brother’s life. Although the brothers were both in France for the two weeks before Frank’s death, duty and the preparations for battle likely prevented them from seeing each other. As an older sister, I wonder how that affected Eli, as the older sibling, and that was just one of the many parts of the war he kept to himself when he returned home.

We shared as a group a ration of rum, just as soldiers would’ve had before going over the top. I made a joke about Frank not being the legal drinking age, at least in Ontario, but I gave him his portion nevertheless. As the others went off to explore the cemetery, I knelt in front of his grave and whispered a few words to him, and then it was goodbye.

*

I’m finishing this blog entry the next day. I’m sitting in my hotel room, looking out at beach where Canadians died fifteen years after Francois’ death on the Somme. I’ve come to a realization today, sitting in the van as we drove to the Normandy coastline. I’m here in France to learn about the war, and that’s something I’ve accomplished in ways I never imagined. I’m seeing history embedded in the landscape of a country my ancestors once called home. But in that cemetery, I wasn’t just presenting a story about a relative I likely wouldn’t have met even if he had come home in 1919.

Instead, I feel like I brought closure to a story, and eased an absence that has endured for three generations. I carried not only my own grief for a young life cut short, but a ninety-year accumulation of tears from generations too poor to visit his grave site in France.

Although I’m still crying (again!) tonight, I don’t think it’s just my own relief I feel. I think it’s Frank’s too.