On June 6, 1944, the allied forces under the Supreme Allied Commander, American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, unleashed a powerful invasion on the French coast at Normandy. The invasion plan had been two years in the making, and was arguably the most complex and massive attack in the history of warfare.

On June 6, 1944, the allied forces under the Supreme Allied Commander, American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, unleashed a powerful invasion on the French coast at Normandy. The invasion plan had been two years in the making, and was arguably the most complex and massive attack in the history of warfare.

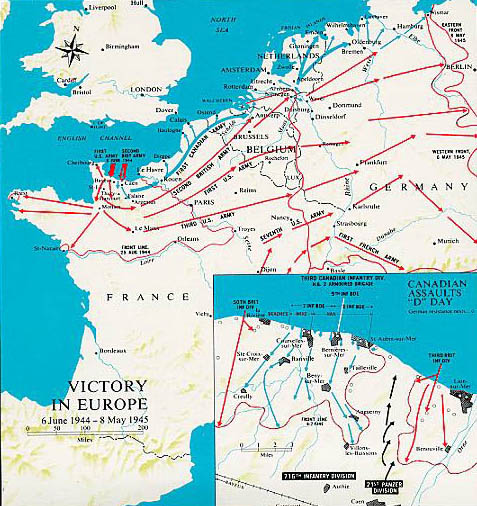

The invasion plan called for five infantry divisions to wade ashore on a fifty mile (eighty kilometre) stretch of the French coast. The British Second Army including units of General H.D.G. Crerar’s First Canadian Army was to form the left side of this front, the First U.S. Army the right. Three airborne divisions, one on the British flank incorporating the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, and two on the American, would precede them to delay enemy movements and facilitate expansion of the bridgehead.

The planners had devised an ingenious way to unload men and huge quantities of supplies and to get petrol to the invaders. Great ingenuity led to Mulberry and Pluto, the first two artificial harbours the size of Dover made from huge concrete caissons and scuttled ships, and the latter a pipeline under the Ocean.

The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, comprising two battalions from each of its 7th and 8th brigades in the first wave, was to hit Juno Beach, sited between the two British landing beaches. Fortified small towns like Courseulles-sur-Mer, St-Aubin, Beny-sur-Mer and Bernières-sur-Mer provided the guts of the German defences on Juno. Once the beach defences were cleared, the advance would press inland. The city of Caen on the Anglo-Canadian front was to be taken the first day.

The hardest struggle was at Omaha Beach where the Americans suffered terrible casualties. Everywhere else, the attackers landed with fewer casualties than feared, the Germans apparently caught by surprise. Their panzer divisions, most well inland, would need time to reach the beaches.

Minesweepers were vital to the success of Allied landings in Normandy. Bangor Class minesweepers of the Royal Canadian Navy, from the beginning of May until D-Day, 6 June 1944, opened up the channels for the Western Task Force landing on Omaha and Utah Beaches. HMCS Caraquet (Commander A.H.G. “Tony” Storrs, RCNR), Cowichan, Malpeque, Fort William, Minas, Blairmore, Milltown, Wasaga, Bayfield and Mulgrave formed the 31st Canadian Minesweeping Flotilla; HMCS Thunder, Vegreville, Kenora, Guysborough, Georgian and Canso joined the British 4th, 14th and 16th Flotillas. Just after midnight on 6 June, using electronic navigation aids of extreme precision, unable to take evasive action if under attack, sometimes within a mile and a half of the German coastal guns, and thus the spearhead for the landings, the 31st, 4th and 14th flotillas off Omaha Beach, and the 16th flotilla off Utah Beach, successfully cleared the assault channels, undetected by the enemy, in spite of moonlight that “provided ample illumination” for the defences of Germany’s vaunted ‘Atlantic Wall.’

Not that the assault was easy. Far from it. Germany’s 716th Inf. Div., which was defending Juno Beach, was no crack unit, but its reinforced concrete bunkers, armed with machine-guns, artillery and 88-millimetre anti-tank guns, were well-sited, mutually supporting, and all but impregnable to gunfire. The underwater and beach defences of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall, their construction speeded by the able and energetic Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, also posed a deadly threat to landing craft and channeled tanks and infantry into designated killing zones.

None of the Canadians—except for a single troop of tanks from the 1st Hussars—reached their D-Day objectives, but all units had moved well inland and were close to joining up with British troops to their east and west. The British D-Day objective of Caen was not reached, however, and would not be for more than a month. In all, the Canadians lost 340 killed in action, 574 wounded and 47 taken prisoner. It was a terrible toll; that it was much less than had been predicted by the planners was little consolation.

Adapted from ”Bloody Normandy” by historian Jack Granatstein, published in Legion Magazine

The Canadian Battlefields Foundation battle bursary students visit the D-Day beaches annually on their study tour of Canadian battle sites in Northern Europe with historians. This is what 2005 Canadian Battlefields Foundation Bursary student Dave Borys, Honours History, University of Alberta, reported:

“Standing at Juno Beach I felt much of the same mixed emotions that I felt at Dieppe. However, the one overriding emotion was pride. Pride in the significance of the victory achieved by the Canadians on that day and pride in the fact that so many people sacrificed so much for the liberation of a country an entire ocean away. That is something remarkable, especially knowing that these were young men my age, the majority of whom had never been to France before, yet were willing to lay down their lives for the freedom of these people. With thoughts like this running through my mind it was appropriate that the weather was overcast with slight rain, it presented an ominous picture of the beaches of Juno. With our group being the only people there, the sound of the surf became the constant reminder of where we stood and what had occurred on that very spot.”