- September 1944: The Leopold Canal

- October-November 1944: Breskens Pocket

- September 1944: Liberation of Antwerp Harbour

- October 1944: The Battle for Woensdrecht and the Neck of the Scheldt Estuary

- October-November 1944: Freeing Walcheren Island

September 1944: The Leopold Canal

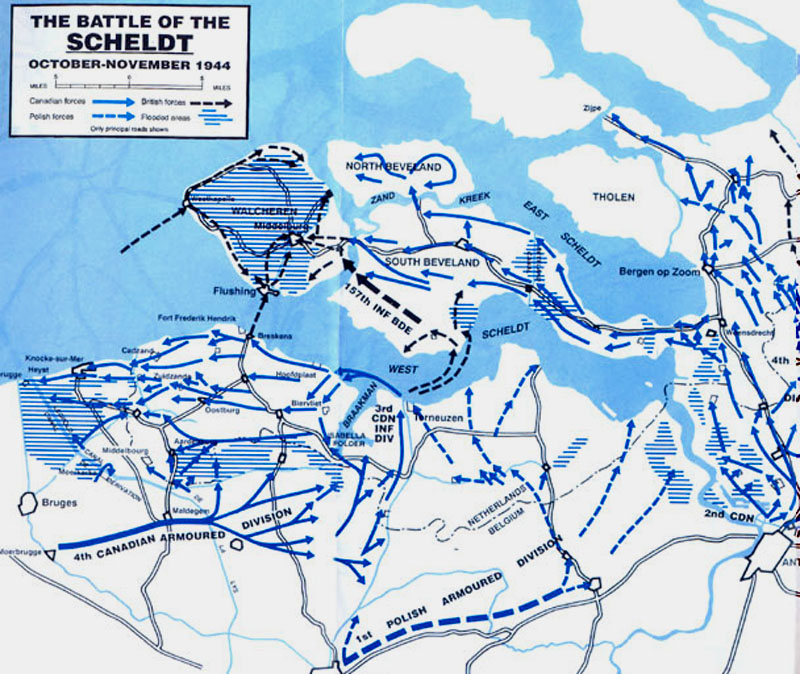

In September 1944, following the rout of the German armies from Normandy, the allied armies of the U.S., Britain and Canada surged eastward from France into Belgium. While reaching the Rhine was their main focus, attention was finally given to the liberation of Antwerp, a port that could handle the vast logistical supply necessary for three armies on the move.

Although the city of Antwerp had fallen to the British, the docks had not been cleared, and the approaches to it along both banks of the Scheldt River were strongly held by the vaunted 15th German Army, who were determined to prevent the Allies from making use of the port of Antwerp. Until the mouth of the Scheldt estuary was closed, Antwerp–60 miles inland–was of no value.

German General Gustav von Zangen, commanding 15th Army, issued an order declaring that: “the defence of the approaches to Antwerp represents a task which is decisive for the further conduct of the war.” The First Canadian Army had three divisions under command: 4th Canadian Armoured (including the Polish Armoured), and the Second and Third Infantry: in all, some 50,000 men. The Fourth Canadian Armoured was ordered to clear a crossing of the Gent Canal at Moerbrugge. The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, supported by the Lincoln and Welland Regiment, struggled for the objective for three days, with heavy casualties.

On the morning of Sept. 10, the engineers completed a bridge. The tanks of the South Alberta Regiment joined the infantry and began flushing the enemy from houses and haystacks. The division was next ordered to do an immediate crossing of the Leopold Canal “to keep the Germans on the move.” The Canadians discovered they were fighting an enemy whose well-organized delay actions and determination revealed just how committed the Germans were to defending the approaches to Antwerp. The Algonquin Regiment had 28 killed, 40 wounded and 66 taken prisoner. The German counterattack employed all available resources, but the Algonquins held on.

The Canadian Grenadier Guards with the Lincoln and Welland Regt. on board led the way to Maldegem on the morning of Sept. 15. The enemy was gone and they continued east past open fields where one day the Commonwealth War Graves Commission would establish the Canadian military cemetery at Adagem where 848 Canadian and 298 Polish and British soldiers lie.

Adapted from an account by historian Terry Copp, published in Legion Magazine

The Canadian Battlefields Foundation battle bursary student Katie Bunting, University of Ottawa Honours History, visited Adegem in 2005. These are her comments:

“My favorite war museum we visited was the Canadian Museum in Adegem-Maldegem. It was built and opened by Mr. Gilbert Van Landschoot in 1995. He had promised his father on his deathbed to create a tribute to the Canadians who had liberated them and to share their war experiences with the younger generations. Over 40 years had passed since their liberation and still no commemoration had been made. Creating the Canadian Museum became Mr. Van Landschoot’s mission. As he spoke to us, his eyes shone brightly and he was incredibly animated. His pride in the museum was contagious. All of the artifacts had been donated and the variety and completeness of the collection was impressive. I wish every Canadian had the opportunity to visit the Canadian War Museum in Belgium. The importance of Canada’s contribution and sacrifice is celebrated so sincerely and passionately. It warmed my heart and filled me with pride.”

October-November 1944: Breskens Pocket

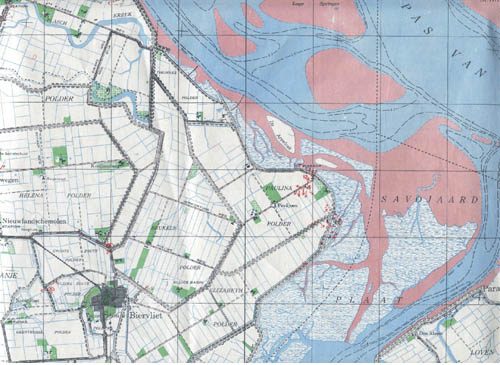

Before any attack on Walcheren could be mounted, the Canadians needed to capture Scheldt Fortress South, which the Canadians called the Breskens Pocket. The task was assigned to 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions.

General Guy Simonds planned Operation Switchback, which called for 9th Brigade. to assault the Breskens Pocket through the back door. Tracked amphibious vehicles known as Buffaloes would enter the water at Terneuzen, which had been captured by the Polish, and then land the brigade on the lightly defended northeast coast near the Dutch town of Hoofdplaat. But for this to work, the enemy’s attention had to remain focused on the Leopold Canal. So, 7th Brigade was ordered to carry out a frontal attack near the main Breskens road.

Switchback was a very risky operation. To succeed it would require surprise, extraordinary courage and maximum fire support from the artillery and air force. Overcast skies in a rainy October were bound to limit the tactical air force. This meant that the gunners had to be especially creative. Brigadier Stanley Todd, artillery commander of the 3rd Canadian. Division, devised a brilliantly conceived plan to support the infantry. Wasp flamethrowers were used for the first time in support of the attack. The air plan for Switchback employed the full resources of 84 Group, Second Tactical Air Force, which was made up of Royal Canadian Air Force and Royal Air Force squadrons and included British, Polish, Norwegian, French and Czech fighter wings.After close to one month of savage fighting in the war’s most miserable conditions of mud and cold, the Canadian “Water Rats,” as Third Div came to be known, drove the Germans from Breskens Pocket.

Adapted from an account by historian Terry Copp, published in Legion Magazine

Canadian Battlefields Foundation battle bursary student Chris Finney, a University of Waterloo MA History and OCE Graduate, was on the Canadian Battlefields Foundation study tour in 2004. These are his comments:

“What I gained personally was an experience that will stay with me for the rest of my life. By traveling to France with such an amazing group of students and leaders through the Battlefield Foundation I was able to take part in something that I wish every Canadian could go through. To walk where Canadians had fought and given their lives is something special. The whole experience will be something that I hope to teach to other young Canadians in the future as I follow my pursuit of a career in teaching at the high school level.”

September 1944: Liberation of Antwerp Harbour

The following is an excerpt from a speech by Canadian Battlefields Foundation founder, the late Brig-Gen Denis Whitaker DSO. Veterans like BGen Whitaker formed the Canadian Battlefields Foundation to educate young Canadians about the service and sacrifices of Canada’s 1.5 million volunteer service men and women in wars of the 20th century.

“On 16 September I arrived in Antwerp for the first time as Commanding Officer of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry. We established our headquarters in the Ford Motor car factory located close to the docks. We were taking over from the Royal Welsh Fusiliers of the 53rd Welsh Division who had earlier occupied the city of Antwerp after capture by the 11th Armoured.

“I hadn’t been there ten minutes when a hawk-nosed Belgian arrived at my headquarters. He introduced himself as “Harry,” otherwise known as Captain Eugene Colson, head of the Underground in the harbor area. He immediately offered the services of some 600 dockworkers that he had organized into a strong Resistance force.

“At that point in the war Antwerp Harbor was of extreme importance in ensuring the defeat of Germany in the West. After landing on the Normandy beaches, the Allies had broken out from their beachhead and desperately needed logistical supplies for the hundreds of thousands of troops. It was absolutely essential that the Allies secure a major port close to the front lines in order to supply these troops and complete the war. Antwerp was the second-largest port in Europe. In order to use the port, the Allies had first to clear the Germans from the area and also establish access via the River Scheldt.

“Col. Eugene Colson, or Harry as he was code-named in the Resistance, along with the 600 members out his battle group, had controlled the harbor since the city of Antwerp was liberated by the 11th British armored division under the command of the great British General, my friend Pip Roberts. The Germans did their best to destroy the port installations and thus prevent the Allies from using it. Harry and his band carried out the task of defending it until our arrival about the 16th of September 1944. During the next 30 days, Harry and I developed a solid relationship based on trust and respect, which led to success in our objective of holding the Harbor.

“While the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade, to which I was attached, was occupied in the Harbor area, 5th and 6th Canadian Brigades had the important tasks of clearing the eastern and northeast sectors around Antwerp before we could advance toward the Dutch border.

“Finally, on the fifth of October, the entire Second Division was poised to plunge across the border into Holland to seal off the South Beveland Peninsula. At the border, their commanders ordered the resistance fighters home. However many, like Col. Colson, rejoined Canadian units and fought through the Dutch polderlands to free the approaches of the River Scheldt. These Belgian patriots fought without uniforms and without pay, and the price was high. In the months of September and October, 87 of their number were killed and 114 were wounded.”

October 1944: The Battle for Woensdrecht and the Neck of the Scheldt Estuary

By the evening of October 11, the Germans had established defences on the Woensdrecht ridge, and the high dike that carried the railway through Beveland to Walcheren Island. They ordered their army reserve – Battle Group Chill – which included 6 Parachute Regiment and several battalions of self-propelled guns, to bar access to Walcheren by holding positions at the village of Woensdrecht, located at the eastern end of the narrow Zuid-Beveland Isthmus connecting the mainland to South Beveland.

For the Canadians, it was not an inviting prospect to attack these positions with six under-strength infantry battalions, a squadron of tanks and artillery regiments that had to ration ammunition. However, Field Marshal Montgomery, under pressure to open the approaches to the port of Antwerp, insisted the advance continue.

This operation, code-named Angus, called for 5th Brigade to employ one battalion to seize the railway embankment with the other two battalions passing through to seal off the route to Walcheren Island. The first phase of the assault would have to be undertaken by the Black Watch. The Maisonneuves were still more than 200 riflemen short and the Calgaries had borne the brunt of the fighting at Hoogerheide.

The attack, made with under strength and under trained men and a flawed battle plan, against a powerful enemy, failed. For the Black Watch, Oct. 13 was Black Friday, the second single-day disaster in the history of the Royal Highland Regt. of Canada. It was not so much the total casualties – 145 – but the ratio of dead-to-wounded that marked the day’s fighting. Fifty-six Black Watch soldiers were killed or died of wounds. Twenty-seven were taken prisoner.

Despite a series of aggressive counter-attacks on the South Saskatchewan Regt. and evidence of further defensive preparations, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry was then ordered to assault Woensdrecht on October 16. To launch another single-battalion attack into the centre of enemy resistance did not seem like a very good idea, but if anyone could take and hold Woensdrecht it was the RHLI.

Lieutenant-Colonel Denis Whitaker, who had won a Distinguished Service Order at Dieppe and who had been wounded in Normandy, had returned to command a battalion that had established an enviable record of success. Whitaker, whose death in May 2001 was widely mourned, was an outstanding and conscientious leader. He was also blessed with seasoned company commanders and veteran non-commissioned officers. Whitaker surveyed the battlefield from the air and sent patrols forward to probe the defences. He insisted upon attacking at night with the support of three field and two medium regiments. A sandbox model of the village and the ridge were used to brief each company and ensure that the men knew exactly what was expected of them.

The attack was completely successful. The village was captured and positions established on the ridge. But with daylight the inevitable enemy counter-attacks started and a battle of attrition ensued. The fighting raged for five days and cost the RHLI 21 killed and 146 wounded. On Oct. 23, 1944 – after two weeks of intense combat – 2nd Division began the advance west to Walcheren Island.

Adapted from an account by historian Terry Copp, published in Legion Magazine

The Canadian Battlefields Foundation battle bursary students visit Woensdrecht and the Scheldt area often on their study tour of Canadian battle sites in Northern Europe with historians. David Gall, Honours History graduate of University of Waterloo:

“Treading the same land that the Canadians visited a lifetime ago under completely different circumstances, and knowing how selflessly those soldiers offered their lives for a cause greater than themselves, I could not help but feel my heart well up with pride in my fellow countrymen. I found myself wondering if I could ever find it in myself to do what they did, if I was asked to offer the greatest sacrifice.”

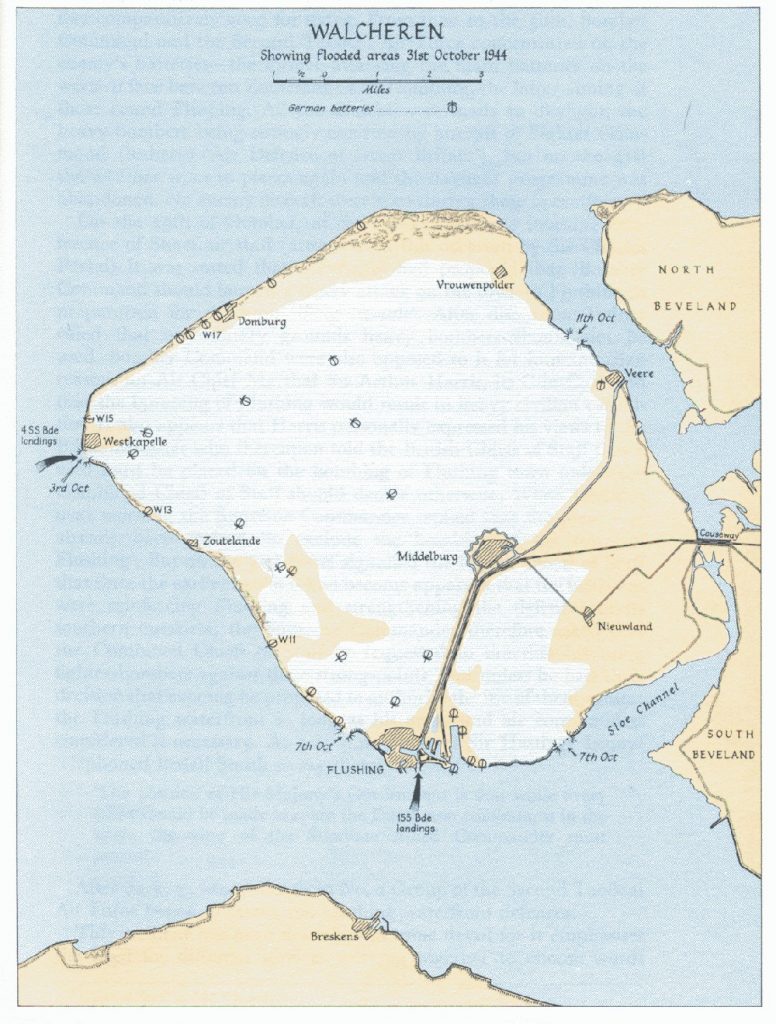

October-November 1944: Freeing Walcheren Island

On October 23, 1944 – after two weeks of intense combat at Woensdrecht – 2nd Division began the advance west to Walcheren Island. Their operations to clear the Beveland Peninsula were carried out swiftly and efficiently. A brigade of the 52nd Lowland Scottish Division launched an amphibious assault across the Scheldt, forcing the enemy to abandon its new defensive line at the Beveland Canal before conducting a hasty retreat to Walcheren. The Scots, their advance slowed by mud, mines and the natural caution of green troops, failed to prevent the exodus.

With just 36 hours to go before the start of the hazardous commando landings at Westkappele and Flushing, on the west coast of Walcheren Island, General Simonds needed immediate action. Fourth Brigade was told to seize enemy positions at the eastern end of the causeway that linked Beveland to the island of Walcheren, and 5th Brigade prepared to capture a bridgehead on the island, which would then be turned over to the Scots.

While the Calgaries rehearsed an assault crossing using storm boats, the Black Watch mounted a probing attack along the straight causeway. The enemy reacted with intense fire, including shells, which “raised water 200 feet high when they fell short.” The Black Watch withdrew and dug in. Engineers, sent to reconnoitre the crossing routes, reported there was not enough water for assault boats to operate – even at high tide. The mud flats were impassable to tracked landing vehicles.

Every November the Calgary Highlanders commemorate Walcheren Day, paying tribute to men who accomplished the impossible. The first Calgary attack faltered when it became clear that the enemy had moved men out onto the causeway. The battalion withdrew until 5th Field Regt. was ready with a new fire plan that employed two regiments on a frontage of just 750 yards.

The barrage was designed to sweep the causeway, lifting 50 yards every two minutes. As dawn broke on November 1st, the Calgaries advanced behind the barrage and got three companies into position on the island. The enemy’s reaction was exactly what Simonds had been hoping for–intense counterattacks on the Canadian bridgehead just as the commando landings got under way on the ocean side of Walcheren.

The Calgaries now began to pay the price of their success. Heavy shelling and a series of counterattacks forced the contraction of the bridgehead. The commando landings, though costly in men’s lives, were going well and the Scots were ready to take over operations the next morning. Fifth Brigade was told to organize a further attack designed to ensure that the bridgehead was secure before handing over. The task was given to Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, which employed two of its three understrength companies. While the Maisonneuve fought their isolated battle, the Scottish engineers found a way onto the island through the mud flats. Infantry, moving slowly in single file, began to establish a second bridgehead and within 24 hours had outflanked the enemy. This forced a rapid enemy retreat. The causeway had cost the Calgaries 17 killed and 46 wounded. The Maisonneuve, with their companies of less than 60 men, had just one fatality and 10 wounded.

On November 28, 1944, after British minesweepers had cleared some 267 mines from its waters, the River Scheldt was opened for shipping. The Canadian-built Fort Cataraquisteamed up the Scheldt to Antwerp harbour, bearing badly needed supplies to the allied armies. The cost, in casualties, over the six-week battle was 12,873 men of First Canadian Army.

Adapted from an account by historian Terry Copp, published in Legion Magazine

Canadian Battlefields Foundation battle bursary student Sharon Roe, a University of Toronto History student, visited the Breskens battle site in 1998. These are her comments:

“If our current generation does not teach proper military history, in another fifty years the Canadian content of this battle is sure to be completely forgotten. Considering the sacrifices, that is a tragic thought.”